Not long ago the Singapore Daily forwarded me the transcript of this interview, by well known criminal lawyer Subhas Anandan to the Singapore Law Review, a journal published by students in the Faculty of Law at NUS:

http://www.singaporelawreview.org/2008/04/interview-with-criminal-lawyer-mr-subhas-anandan/

In the interview, Mr Anandan disclosed about what is already well known in Singapore, the law inherently favours the prosecution, and by extension, the police. He argues for more access by lawyers with their clients under custody, and for a magistrate to be present when an accused pens his statement, especially in capital cases to ensure it's fairly given.

Subhas Anandan, current head of the Law Society's criminal defense lawyers association is championing for a more transparent system.

I disagree and agree with Mr Anandan on that score. I don't think lawyers should have immediate access to their clients when an accused is first arrested and detained for police investigations. By law the police must charge an accused in court within 48 hours, thereafter they can have him remanded in the station for further investigations. Only when these investigations are completed, with the accused released on bail or detained in the state prison, will the defense lawyer be granted access. I think this policy should remain in force.

In most western democracies, notably the UK whose legal system we follow/inherited, lawyers can have immediate access to their clients and those accused have to be cautioned when arrested - that they have a right to counsel and know the charge they are facing. However a key point is also conveyed, they have to disclose what they want to use in their defense and its' less likely to be believed if they hold it back until their trial. It's roughly the same here, an accused when formally charged is cautioned to disclose what he intends to say to the charges. The UK's formal caution reads:

You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defense if you do not mention when questioned, something which you later rely on in court.Anything you do say, may be given in evidence.

I don't think lawyers should get immediately involved especially when investigations are not completed. The police might need to find out more about the crime and secure evidence or detain accomplices. Getting a lawyer in at this stage might cause many accused to become uncooperative. In cases where an accused is believed to be involved in a series of offences, this could derail the investigations and leave many crimes unsolved.

The system has to work both ways and the police and prosecutors must be allowed first crack at the accused. It does not trample on his rights, just because he doesn't have immediate access to legal counsel. An accused can still choose to remain silent and be uncooperative, and it's still the prosecutors job to prove his guilt in court. Rather the problem lies with what an accused may or may not have said during these initial investigations or interrogations.

In Singapore, the accused is not usually cautioned until the final bit, where he is formally presented with the charges the police are preferring on him. When he is first interviewed and his statements recorded, he is not cautioned that he is not obliged to incriminate himself. And upon completion when he is invited to sign these statements, he is also asked to counter-sign that he was not coerced, threatened or promised anything when making these statements. These statements are kept by the police and prosecutors and is not offered to the accused or defense counsel unless they intend to use it court. Either way, the defense only gets this at a latter stage. Instead the defense will only initially get a copy of the formal charges and the accused's response to them. When the police are satisfied that they have enough to charge the accused in court, only then will the caution under Sec 23 (1) of the Criminal Procedure Code be invoked. The procedure is thus:

1) The charge is specified and presented (or read) to the accused

2) The accused is then cautioned as follows:

Do you want to say anything about the charges that was just read to you? If you keep quiet now about any fact or matter in your defense and you reveal this fact or matter only at your trial, the judge may be less likely to believe you. This may have a bad effect on your case in court. Therefore it may be better for you to mention such fact or matter now. If you wish to do so, what you say will be written down, read back to you for any mistakes to be corrected and then signed by you.

There is usually no dispute on the formal presentation of the charge or the accused's response which is duly recorded. The police and prosecutors will rely more on the earlier statements than on this Sec 23(1) caution. The dispute is almost always on those earlier statements, especially if they contain therein an admission or an incriminating point. Quite often in court you will see the accused recanting their statements or admissions and alleging that some form of coercion or even threat/violence was used. Unfortunately the law here seems to be against them, more often than not these statements will be admitted into evidence unless they can prove the police officer is lying, or acting with malice against them. Sometimes they might not even fully understand the intricacies of the case and just sign the admission based on what the officers tell them. And when the case comes to trial, they have a hard time disproving this, basically its the word of the officer against theirs.

I'm not saying all or even a majority of police statements are derived through some degree of wrongdoing or unfairly obtained, but I do feel there is a tiny portion of them that are. Of course proving this is next to impossible, unless you can find a police officer willing to testify to this. In the bad old days, some policemen resorted to using violence to obtain confessions, but I think these are extremely rare these days. Perhaps some form of trickery or coercion is made instead, telling an accused they might lower the charges if he admits or tell him that failing to confess will provoke additional charges. Of course I can't prove this, nobody can unless one is privy and present at the recording of the statements. In the SMRT bus drivers strike case, the accused claimed they were assaulted during interrogations. These were later proven false, but I do wonder if some form of coercion took place. I am not casting a slur on the credibility of the police force, but as long as the status quo remains the same, it will always be plausible that in some police interviews and interrogations, something improper has taken place.

Ex-SMRT bus driver, He Jun Ling when arrested for striking, alleged police brutality.

There is a very easy way to remove any doubts on this possibility - to have all interactions between officers and accused persons recorded or taped. Is this too difficult or cumbersome, even expensive? Perhaps 10,15 or 20 years ago, it might ring true, but in the digital age? I think not. In fact the best proof that it is workable lies in another police procedure that has gone digital - the retaining of personal property and valuables of accused persons in detention.

Whenever a person is arrested and before he's placed in the lockup or even when he is sentenced to jail, his property is displayed before him and photographed or videotaped in some instances. Now why have the police/prison department done this for personal property? Very simple - to prevent any allegation of police/prison officers stealing the valuables or to deal with any claim that the accused says he has such and such an item, and it's not there when his property is returned to him. Previously these items were merely recorded and counter-signed by the accused, but now there's the additional safeguard of it being recorded and filmed.

So if the police can take measures to 'cover their asses', to use a crude but apt description, why not do the same for investigations? Instead of having police officers coming to court to deny allegations made against them by an accused person, why not just play the tape and prove once and for all whether it's true or not? There's no need for a police officer to offer an explanation or describe the circumstances in which a statement is taken, a video recording will show all these. Better still it will allow a judge to get the whole picture, not just the statement itself but all facial expressions and the surroundings. The judge and everyone in court can see whether the police officer was menacing, whether the accused was in a drugged or drunken stupor, whether he was left shivering in a freezing room etc.

In 18 US states this is being done, I believe in the UK as well. In the latter if no video recording is present, the interviews must be at least taped. Doing this here will not impede police investigations, rather it will ensure that police officers abide by the laws and procedures in place. If they are doing nothing wrong, why should they worry about the recordings in the first place? Moreover these recordings will not come to light unless an accused challenges the statements he gave in court or alleges some form of violence against him.

A suspect being interviewed by a Police Officer in the US state of Florida.

Storing these videos will also not be a problem, once the trial and appeal process is exhausted it can be wiped clean, re-used or disposed off. I believe banks must keep videos of what transpires on their premises for a period of 6 months, unless of course it becomes subject of an enquiry. Police videos can also follow the same route. Better still when an accused pleads guilty and does not appeal within the prescribed period, these videos no longer require storage. For trials it will be kept for the duration of it until a verdict is delivered. If no appeal is lodged by either the prosecution or defense, it's no longer needed.

There is also 1 other benefit in having these recordings. In 'cold cases' - where a suspect is arrested but not charged perhaps due to a lack of evidence, any future investigations down the road, will allow the current investigation team to re-look the investigations done by their predecessors, and perhaps unearth something the accused said that was missed. Or if the accused is arrested for another similar offense later on, what he said earlier could prove useful in the present case.

Police Commissioner Ng Joo Hee wants to play 'Big Brother' by having video cameras everywhere. Perhaps he should start in his own house!

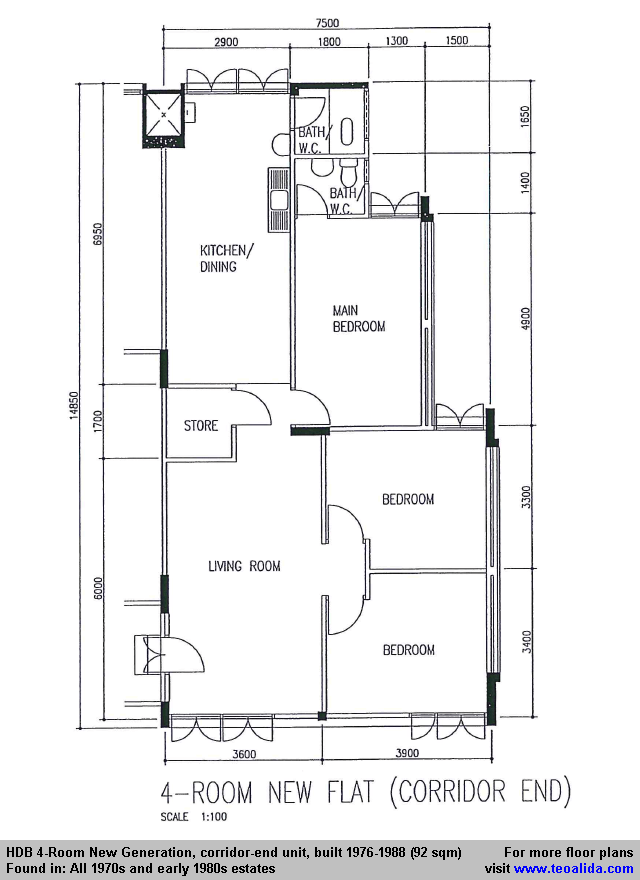

Basically I can find no good reason aside from cost, why police interactions with an accused should not be recorded. Even with costs, I don't think it would be so enormous that we are unable to afford it. The Police Commissioner has stated he wants to have video cameras in every HDB block in future and at various parts of the island. Traffic Police wants to place 300 speed cameras next year and LTA is doing the same to tackle illegal parking. So why not have cameras present at the 1 place in the police station where it can play a very significant part - the interview/interrogation room?

After a trial run earlier this year, you'll soon be seeing more speed cameras like the one above at traffic junctions.

By not having cameras, the possibility that something improper is done by police officers will always be subject to speculation. By having cameras, there will be no confusion or doubt as to what transpired or what was said by whom. The legality of statements derived from accused persons will be clear to all especially the judge presiding at trial. If police officers acted improperly, they will be taken to task - we certainly do not need police officers taking matters into their own hands in our police force. If the accused admitted to his statements, he won't be able to worm his way out of them. This is a win-win situation for justice in Singapore. As it's often said justice must not only be done, but seen to be done, having video cameras in interrogation and interview rooms is definitely a step in that direction.

http://www.singaporelawreview.org/2008/04/interview-with-criminal-lawyer-mr-subhas-anandan/

In the interview, Mr Anandan disclosed about what is already well known in Singapore, the law inherently favours the prosecution, and by extension, the police. He argues for more access by lawyers with their clients under custody, and for a magistrate to be present when an accused pens his statement, especially in capital cases to ensure it's fairly given.

Subhas Anandan, current head of the Law Society's criminal defense lawyers association is championing for a more transparent system.

I disagree and agree with Mr Anandan on that score. I don't think lawyers should have immediate access to their clients when an accused is first arrested and detained for police investigations. By law the police must charge an accused in court within 48 hours, thereafter they can have him remanded in the station for further investigations. Only when these investigations are completed, with the accused released on bail or detained in the state prison, will the defense lawyer be granted access. I think this policy should remain in force.

In most western democracies, notably the UK whose legal system we follow/inherited, lawyers can have immediate access to their clients and those accused have to be cautioned when arrested - that they have a right to counsel and know the charge they are facing. However a key point is also conveyed, they have to disclose what they want to use in their defense and its' less likely to be believed if they hold it back until their trial. It's roughly the same here, an accused when formally charged is cautioned to disclose what he intends to say to the charges. The UK's formal caution reads:

You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defense if you do not mention when questioned, something which you later rely on in court.Anything you do say, may be given in evidence.

I don't think lawyers should get immediately involved especially when investigations are not completed. The police might need to find out more about the crime and secure evidence or detain accomplices. Getting a lawyer in at this stage might cause many accused to become uncooperative. In cases where an accused is believed to be involved in a series of offences, this could derail the investigations and leave many crimes unsolved.

The system has to work both ways and the police and prosecutors must be allowed first crack at the accused. It does not trample on his rights, just because he doesn't have immediate access to legal counsel. An accused can still choose to remain silent and be uncooperative, and it's still the prosecutors job to prove his guilt in court. Rather the problem lies with what an accused may or may not have said during these initial investigations or interrogations.

In Singapore, the accused is not usually cautioned until the final bit, where he is formally presented with the charges the police are preferring on him. When he is first interviewed and his statements recorded, he is not cautioned that he is not obliged to incriminate himself. And upon completion when he is invited to sign these statements, he is also asked to counter-sign that he was not coerced, threatened or promised anything when making these statements. These statements are kept by the police and prosecutors and is not offered to the accused or defense counsel unless they intend to use it court. Either way, the defense only gets this at a latter stage. Instead the defense will only initially get a copy of the formal charges and the accused's response to them. When the police are satisfied that they have enough to charge the accused in court, only then will the caution under Sec 23 (1) of the Criminal Procedure Code be invoked. The procedure is thus:

1) The charge is specified and presented (or read) to the accused

2) The accused is then cautioned as follows:

Do you want to say anything about the charges that was just read to you? If you keep quiet now about any fact or matter in your defense and you reveal this fact or matter only at your trial, the judge may be less likely to believe you. This may have a bad effect on your case in court. Therefore it may be better for you to mention such fact or matter now. If you wish to do so, what you say will be written down, read back to you for any mistakes to be corrected and then signed by you.

There is usually no dispute on the formal presentation of the charge or the accused's response which is duly recorded. The police and prosecutors will rely more on the earlier statements than on this Sec 23(1) caution. The dispute is almost always on those earlier statements, especially if they contain therein an admission or an incriminating point. Quite often in court you will see the accused recanting their statements or admissions and alleging that some form of coercion or even threat/violence was used. Unfortunately the law here seems to be against them, more often than not these statements will be admitted into evidence unless they can prove the police officer is lying, or acting with malice against them. Sometimes they might not even fully understand the intricacies of the case and just sign the admission based on what the officers tell them. And when the case comes to trial, they have a hard time disproving this, basically its the word of the officer against theirs.

I'm not saying all or even a majority of police statements are derived through some degree of wrongdoing or unfairly obtained, but I do feel there is a tiny portion of them that are. Of course proving this is next to impossible, unless you can find a police officer willing to testify to this. In the bad old days, some policemen resorted to using violence to obtain confessions, but I think these are extremely rare these days. Perhaps some form of trickery or coercion is made instead, telling an accused they might lower the charges if he admits or tell him that failing to confess will provoke additional charges. Of course I can't prove this, nobody can unless one is privy and present at the recording of the statements. In the SMRT bus drivers strike case, the accused claimed they were assaulted during interrogations. These were later proven false, but I do wonder if some form of coercion took place. I am not casting a slur on the credibility of the police force, but as long as the status quo remains the same, it will always be plausible that in some police interviews and interrogations, something improper has taken place.

Ex-SMRT bus driver, He Jun Ling when arrested for striking, alleged police brutality.

There is a very easy way to remove any doubts on this possibility - to have all interactions between officers and accused persons recorded or taped. Is this too difficult or cumbersome, even expensive? Perhaps 10,15 or 20 years ago, it might ring true, but in the digital age? I think not. In fact the best proof that it is workable lies in another police procedure that has gone digital - the retaining of personal property and valuables of accused persons in detention.

Whenever a person is arrested and before he's placed in the lockup or even when he is sentenced to jail, his property is displayed before him and photographed or videotaped in some instances. Now why have the police/prison department done this for personal property? Very simple - to prevent any allegation of police/prison officers stealing the valuables or to deal with any claim that the accused says he has such and such an item, and it's not there when his property is returned to him. Previously these items were merely recorded and counter-signed by the accused, but now there's the additional safeguard of it being recorded and filmed.

So if the police can take measures to 'cover their asses', to use a crude but apt description, why not do the same for investigations? Instead of having police officers coming to court to deny allegations made against them by an accused person, why not just play the tape and prove once and for all whether it's true or not? There's no need for a police officer to offer an explanation or describe the circumstances in which a statement is taken, a video recording will show all these. Better still it will allow a judge to get the whole picture, not just the statement itself but all facial expressions and the surroundings. The judge and everyone in court can see whether the police officer was menacing, whether the accused was in a drugged or drunken stupor, whether he was left shivering in a freezing room etc.

In 18 US states this is being done, I believe in the UK as well. In the latter if no video recording is present, the interviews must be at least taped. Doing this here will not impede police investigations, rather it will ensure that police officers abide by the laws and procedures in place. If they are doing nothing wrong, why should they worry about the recordings in the first place? Moreover these recordings will not come to light unless an accused challenges the statements he gave in court or alleges some form of violence against him.

A suspect being interviewed by a Police Officer in the US state of Florida.

Storing these videos will also not be a problem, once the trial and appeal process is exhausted it can be wiped clean, re-used or disposed off. I believe banks must keep videos of what transpires on their premises for a period of 6 months, unless of course it becomes subject of an enquiry. Police videos can also follow the same route. Better still when an accused pleads guilty and does not appeal within the prescribed period, these videos no longer require storage. For trials it will be kept for the duration of it until a verdict is delivered. If no appeal is lodged by either the prosecution or defense, it's no longer needed.

There is also 1 other benefit in having these recordings. In 'cold cases' - where a suspect is arrested but not charged perhaps due to a lack of evidence, any future investigations down the road, will allow the current investigation team to re-look the investigations done by their predecessors, and perhaps unearth something the accused said that was missed. Or if the accused is arrested for another similar offense later on, what he said earlier could prove useful in the present case.

Police Commissioner Ng Joo Hee wants to play 'Big Brother' by having video cameras everywhere. Perhaps he should start in his own house!

Basically I can find no good reason aside from cost, why police interactions with an accused should not be recorded. Even with costs, I don't think it would be so enormous that we are unable to afford it. The Police Commissioner has stated he wants to have video cameras in every HDB block in future and at various parts of the island. Traffic Police wants to place 300 speed cameras next year and LTA is doing the same to tackle illegal parking. So why not have cameras present at the 1 place in the police station where it can play a very significant part - the interview/interrogation room?

After a trial run earlier this year, you'll soon be seeing more speed cameras like the one above at traffic junctions.

By not having cameras, the possibility that something improper is done by police officers will always be subject to speculation. By having cameras, there will be no confusion or doubt as to what transpired or what was said by whom. The legality of statements derived from accused persons will be clear to all especially the judge presiding at trial. If police officers acted improperly, they will be taken to task - we certainly do not need police officers taking matters into their own hands in our police force. If the accused admitted to his statements, he won't be able to worm his way out of them. This is a win-win situation for justice in Singapore. As it's often said justice must not only be done, but seen to be done, having video cameras in interrogation and interview rooms is definitely a step in that direction.